What is a Nutrient Deficiency?

Unlike diseases caused by fungi or bacteria, a nutrient deficiency is a physiological disorder. Think of it as malnutrition for your plants. It occurs when a plant cannot get a sufficient amount of an essential nutrient needed to grow, function, and thrive. Plants require 17 essential elements for healthy growth, and a shortage of even one can cause serious problems.

This "disease" isn't caused by a pathogen. Instead, the cause is environmental. It can happen for two main reasons:

- Simple Deficiency: The nutrient is simply not present in the soil in sufficient quantities. This is common in sandy soils or gardens that have been heavily planted for years without being replenished.

- Nutrient Lockout: The nutrient is in the soil, but the plant can't absorb it. The most common cause of this is an improper soil pH. If your soil is too acidic or too alkaline, certain nutrients become chemically "locked up" and unavailable to plant roots, no matter how much is present.

All plants can suffer from nutrient deficiencies, but some are more prone to specific issues. For example, tomatoes are famous for blossom-end rot (a calcium issue), and acid-loving plants like azaleas and blueberries will quickly show iron deficiency in alkaline soils.

How Deficiencies Develop

A nutrient deficiency doesn't "spread" from one plant to another like a contagious disease. Instead, it develops in a plant when its need for a nutrient outpaces the soil's ability to supply it. This often happens during periods of rapid growth, like in the spring or when a vegetable plant begins to produce fruit.

A key clue to diagnosing a deficiency is understanding "nutrient mobility." Some nutrients are mobile within the plant, while others are immobile.

- Mobile Nutrients (like Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium): A plant can move these nutrients from its older, lower leaves to its new, growing tips. Therefore, deficiency symptoms for mobile nutrients will appear on the older, lower leaves first.

- Immobile Nutrients (like Calcium, Iron, Boron): A plant cannot move these nutrients once they are in place. If a shortage occurs, the new growth cannot get what it needs from the older leaves. Therefore, deficiency symptoms for immobile nutrients will appear on the newest, upper leaves and growing tips first.

The deficiency will persist and worsen as long as the underlying soil condition—either a lack of the nutrient or an improper pH—is not corrected.

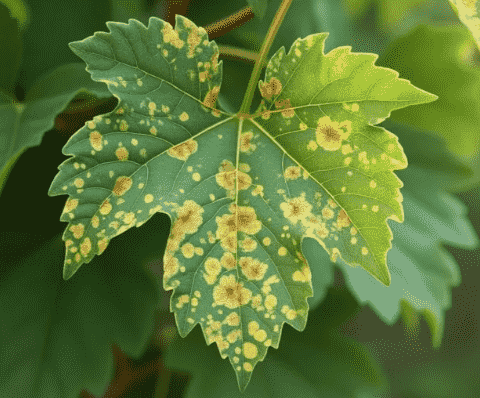

Symptoms

Learning to read the signs your plants give you is the first step to solving the problem. The location of the symptom (old leaves vs. new leaves) is your most important clue.

Early Stage

- A general lack of vigor or slightly slower growth compared to other plants.

- A subtle loss of deep green color; leaves may look a bit pale.

- Slight discoloration may begin to appear on the edges of either the oldest or newest leaves.

Middle Stage - Key Diagnostic Signs

- General Yellowing of OLD Leaves (Nitrogen): The entire leaf, veins and all, on the lower part of the plant turns a pale yellow.

- Yellow Edges on OLD Leaves (Potassium): The outer margins of the lower leaves turn yellow, then brown and crispy, while the center of the leaf stays green.

- Purplish Tint on Leaves (Phosphorus): Plants, especially young ones, may develop a purplish cast on their leaves. Growth is often stunted.

- Yellowing Between Veins on NEW Leaves (Iron): This is called "interveinal chlorosis." The newest leaves at the top of the plant turn yellow, but the veins remain a distinct dark green.

- Stunted, Deformed NEW Growth (Calcium/Boron): The newest leaves and buds are small, misshapen, or die back. Blossom-end rot on tomatoes is a classic sign of a calcium transport problem.

Late Stage

- Discolored areas on leaves turn brown, die, and may fall out, leaving holes.

- Affected leaves wither and drop off the plant, leading to significant defoliation.

- The plant is severely stunted, produces few or no flowers, and yields little to no fruit.

How to Control Disease Progression

Once you suspect a nutrient deficiency, you need a two-pronged approach: provide a quick fix to help the plant now and a long-term solution to fix the underlying soil problem.

- Get a Soil Test: This is the single most important action. A simple home pH test can tell you if that's the problem. A lab soil test from your local extension service is even better, as it will tell you your pH and the exact levels of key nutrients.

- Provide a Quick Fix: Apply a liquid fertilizer that is quickly absorbed. A foliar feed (spraying the leaves) with a product like liquid kelp or fish emulsion can give the plant a fast-acting dose of micronutrients to help it start to recover.

- Correct the Root Cause: The quick fix is temporary. The long-term solution involves amending your soil based on your soil test results. This could mean adjusting pH or adding specific nutrients.

- Check Your Watering: Overly wet, waterlogged soil prevents roots from breathing and absorbing nutrients. Ensure your soil has good drainage and you are not overwatering.

Treatment Options

Treatment involves giving the plant what it needs and fixing the soil so it can access it. Remember, damaged leaves will not turn green again; look for improvement in the new growth.

Organic Treatment Methods

- For a Quick Boost: Use a water-soluble feed like fish emulsion, compost tea, or liquid kelp.

- For Nitrogen (N): Top-dress with compost, manure, or a seed meal like alfalfa meal or blood meal.

- For Phosphorus (P): Amend soil with bone meal or rock phosphate.

- For Potassium (K): Amend with greensand, kelp meal, or wood ash (use wood ash sparingly and only in acidic soil).

- For Iron (Fe): Apply chelated iron, which is a form that is readily available to plants even in higher pH soils.

Chemical Treatment Options

- Balanced Fertilizers: A general-purpose fertilizer like a 10-10-10 provides equal amounts of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium.

- Water-Soluble Fertilizers: Products like Miracle-Gro provide a very fast, but short-lived, dose of nutrients.

- Specific Nutrient Fertilizers: You can buy fertilizers that provide just one nutrient, such as Ammonium Sulfate (for Nitrogen) or Iron Sulfate (for Iron and to lower pH).

Step-by-Step Treatment Procedure

- Identify the likely deficiency based on symptoms and their location.

- Confirm your suspicion with a soil pH test, and ideally, a full lab test.

- Apply a fast-acting liquid fertilizer to the plant's leaves and soil for immediate relief.

- Based on test results, amend your soil for the long term. If pH is the issue, add lime to raise it or elemental sulfur to lower it. If a specific nutrient is low, add a slow-release organic or granular fertilizer.

- Water the amendments into the soil.

Expected Timeline for Recovery

With a liquid feed, you should see improvement in the color and vigor of new growth within one to two weeks. Soil amendments are a long-term fix and will provide sustained health for the rest of the season and into the future.

Prevention Strategies

The best way to treat nutrient deficiencies is to prevent them from ever happening. The secret is not to feed the plant, but to feed the soil.

- Build Healthy Soil: This is the number one rule. Regularly amend your garden beds with several inches of high-quality compost or other organic matter. Healthy soil is teeming with microbial life that makes nutrients available to plants.

- Get a Baseline Soil Test: Before starting a new garden, get a soil test. This tells you your starting point and allows you to make corrections before you even plant. Repeat every 3-5 years.

- Mulch Your Garden: A 2-3 inch layer of organic mulch (like shredded leaves, straw, or wood chips) breaks down over time, slowly releasing nutrients into the soil. It also helps retain moisture and regulate soil temperature.

- Practice Crop Rotation: In vegetable gardens, rotating where you plant different families of crops each year prevents the depletion of specific nutrients from one spot.

- Use Cover Crops: Planting a cover crop like clover or winter rye in the off-season is a fantastic way to prevent soil erosion, add organic matter, and, in the case of legumes like clover, add nitrogen back into the soil naturally.